The leading cause of death worldwide, according to the WHO, is ischemic heart disease. Number 2 is stroke. The third is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Trends in urbanization, air pollution and tobacco use lead to a 14% increase in COPD deaths from 2010 to 2019. Three million three hundred thousand people died from COPD in 2019. COPD cases are projected to expand fivefold, to 592 million in 2050, with the burden falling heavily on women in lower-middle income countries.

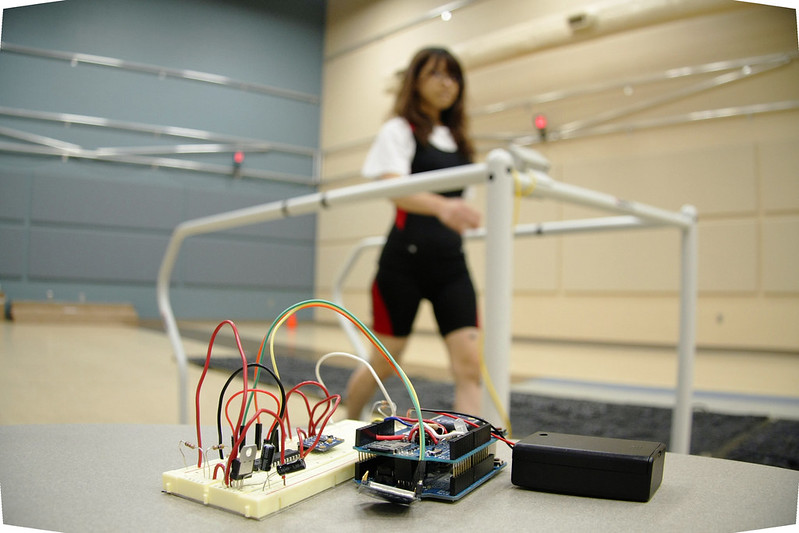

Biomechanics researchers at the University of Nebraska at Omaha are in the early stages of developing a working prototype for a device that could one day detect an imminent exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, before any obvious symptoms are present. (Photos: Charlie Litton, UNeMed)

COPD is a disorder that comes from damage to the delicate tissue in the lungs. Patients experience COPD as worsening shortness of breath, increased mucus production in the airway, and coughing. Even among the complexities of human biology, COPD is complicated.

It also has no cure. While treatment options help slow the progression of the disease, people suffering from COPD currently have little hope of recovering lost function in their lungs. Living with COPD means planning your day around bouts of shortness of breath. Over time, those plans require longer rest breaks for less vigorous activity.

Then there are exacerbations.

A sudden worsening of symptoms or an exacerbation may require hospitalization or even a stay in the ICU. Not to minimize the enormous emotional toll that a sudden inability to breathe produces in a person – COPD exacerbations drove the cost of COPD, just in the United States, to $49 billion in 2020.

From these stark numbers, one thing is clear: current treatment of COPD is not working. The millions of people who now and will suffer from a disease that steals the very air from their lungs have few good options. They need a better way.

Dr. Jenna Yentes, a biomechanist from the University of Nebraska Omaha, seems to have found one. She observed that the regulation of breathing and walking – the invisible process by which your body responds to exercise by breathing harder – is uniquely broken in people with COPD. Jenna’s lab tracked COPD patients in an advanced motion capture laboratory and found a pattern. Their breathing lagged to catch up with their walking. The more severe their disease, the more pronounced the pattern. People without COPD, even when they’re tired, out of shape, or impaired, do not have the same pattern of dysfunction.

Working with UNeTech, Jenna led a multi-site clinical study across 3 states. Her lab built a prototype device that replaced the high-end motion capture system with a pedometer and an elastic band that patients can wear around their chests. After months of research, hours of troubleshooting, and countless mailed SD cards, the study replicated her results from the lab. The pattern of dysfunction could be seen, with lower resolution, in the field.

It… worked.

Jenna’s study demonstrated that an inexpensive wearable device could capture the data that tracks the real-time progression of COPD. Such a device opens all kinds of compelling opportunities: better management of symptoms, more targeted measurement of treatments, and, possibly, the prediction of exacerbations. In the clinical study, there seemed to be a particular kind of worsening in the dysfunction, the inability of COPD patients’ ability to synch their breathing and walking, before they have an exacerbation.

The scope of Dr. Yentes’s accomplishments cannot be overstated. On the slimmest of shoestring budgets, Jenna had conducted a national study that served as a breath of hope for millions of people suffering from a truly terrible disease. The pilot data also helped to attract a team of international entrepreneurs that would go on to found a startup around her invention – RespirAI.

But that’s another story…