Who owns the inventions made from university research? It is a fundamentally technical question that seems best answered by serious people wearing dark suits, possibly on weekend C-SPAN. It is the sort of question you likely need three different reference books and a transcript of a congressional debate to answer with true detail and appreciation. What inspiration can we draw from such a dry, albeit important question?

Don’t be fooled. The answer is far more fundamental to our democracy than it first belies.

To cut to the chase, universities (or federal laboratories) own the title to intellectual property produced from research funded by the federal government. Look at the patents invented by university faculty. They’re typically owned by the Board of Regents or ‘ the Board of Trustees of the university that employs the inventor. The Jeffersonian rationale behind the Bayh-Dole Act is an interesting story, but it answers a different question. That’s “HOW are patents produced from university research owned?” – it’s not quite the same as “WHO owns the inventions made from university research?”.

The patents, owned by universities and laboratories, are intended to kickstart the innovation economy. Their ownership serves a public cause, and by most measures, the public has been well served. Authors get downright hyperbolic about what a good idea the Bayh-Dole act was. Its legacy, promoted by many, many organizations, has rare bipartisan support. I believe the popularity of the Bayh Dole Act may reflect just how artfully it answered the fundamental question: who owns the inventions made from university research?

The public. You and I own the inventions made from university research. Taxpayers spend 80 billion dollars on research every year and the inventions made from that work are a public good. Bayh-Dole assembled a coalition of stakeholders, beneficiaries, and processes that are the democratic compromise by which people are likely to get the most value from those assets. Giving title to universities, with some strings attached, served to be the best means to embody that ownership. It was the best, not the perfect way to get meaningful use of those assets our federal dollars continue to create.

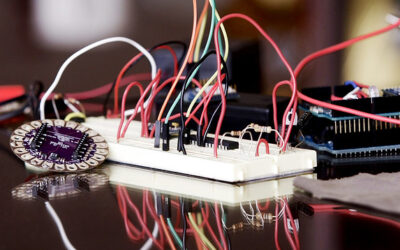

Because getting value from university intellectual property is really, really difficult. It is in that challenge, however, that I see the real public benefit occur. The endless labor of prototyping, revising, strategizing, starting up, pivoting, funding, and, ultimately, succeeding will transform our economy. Getting that value is difficult because it involves so much work. That work, however, provides endless opportunities to teach and learn. Students, colleagues, and inventors all enrich their lives by learning the work it takes to go from invention to product to enterprise. On top of that, we all gain the benefit of the value of intellectual property to enrich our commonwealth of innovation.

Technology entrepreneurship is powerfully transformative. It can serve to consolidate wealth in troubling ways. The commonwealth of innovation does not solve that problem entirely. Part of the ongoing popularity of Bayh-Dole, however, reflects a rare democratic consensus that points to part of a solution. Working together to advance inventions resulting from federal research creates a democratically-recognized commonwealth of innovation where the power of technology entrepreneurship can create true public good.