Part 1: A Jeffersonian Solution

In this series, Jace Gatzemeyer discusses the history, goals, successes, and challenges of technology transfer. Dr. Gatzemeyer is UNeTech’s Innovation Development Strategist, and one aspect of his job involves seeking early-stage funding for prelaunch startups formed around the most innovative and commercially viable inventions from Nebraska research institutions. This installment looks at the early history of tech transfer.

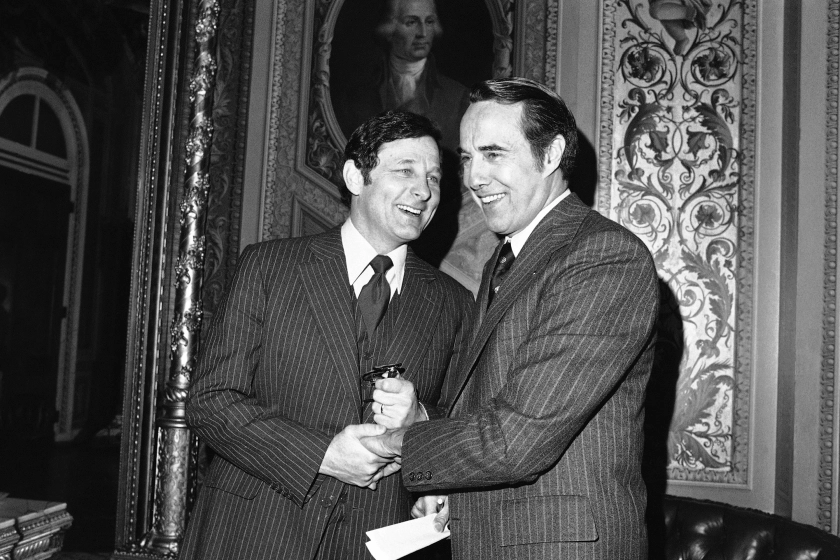

Senators Birch Bayh and Bob Dole at the U.S. Capitol on Feb. 21, 1978. The Bayh-Dole Act has helped private drug companies bring government pharmaceutical research to market—saving lives, writes Betsy de Parry. John Duricka—AP Images

In a previous “What is…” post, UNeTech’s Associate Director Joe Runge explained Technology Transfer with the help of Dr. Michael Dixon, President and CEO of UNeMed, the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Technology Transfer Office. Dr. Dixon explained that, in the context of research institutions, technology transfer is the process by which new inventions and other innovations created in those institutions’ labs are turned into products and commercialized.

But tech transfer is still a relatively young concept, only born in 1980. How did it come into existence? Well, the idea of tech transfer as we understand it today emerged as a response to the worrying economic downturn of the mid-1970s. As the post-World War II economic boom came to an end, the United States found itself slipping into industrial irrelevance as newly industrialized economies like Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea became increasingly competitive in science and technological innovation.

Thanks in part to an influential report by Vannevar Bush, “Science The Endless Frontier,” which argued that scientific progress was an essential key to “our security as a nation, to our better health, to more jobs, to a higher standard of living, and to our cultural progress,” the U.S. in the ‘70s was investing more than $75 billion in government sponsored R&D. But how could this technological innovation best be managed? As Ashley J. Stevens describes it, there were several competing schools of thought in this regard.

Most prominently, there was “a Hamiltonian belief that the solution lay with a strong central government, which should take charge and actively manage these resources,” in contrasting with “a Jeffersonian belief that the solution lay with the individual and that the best thing government could do to provide incentives for success was to get out of the way of these individuals.”

The Carter Administration and its allies supported the Hamiltonian plan, arguing that “government contractors — including small businesses and universities — should not be given title to inventions developed at the government expense.” But the Jeffersonians, led by Senators Birch Bayh (D., IN) and Robert Dole (R., KS), made a strong case for “getting out of the way,” showing that the current state of affairs, in which the government retained titles to inventions created using government funding, had led to the accumulation of 28,000 patents with fewer than 5% commercially licensed.

With the momentum on their side, Senators Bayh and Dole introduced a landmark piece of legislation aimed at changing the way ownership would be managed for inventions made with federal funding. Introducing the Bill to the Senate in 1978, Senator Bayh said:

A wealth of scientific talent at American colleges and universities — talent responsible for the development of numerous innovative scientific breakthroughs each year — is going to waste as a result of bureaucratic red tape and illogical government regulation…. The problem, very simply, is the present policy followed by most government agencies or retaining patent rights to inventions.

The Bayh-Dole Act would devolve responsibility for commercializing the results of federally funded research to the local level by giving responsibility and control to the universities that had carried out the research. Essentially, universities would be enabled to own the patents arising from federal research grants.

The Carter Administration developed its own plan, arguing that “the economy was really driven by large companies and their exclusion from Bayh-Dole was a major weakness in that bill.” However, advocates for letting big businesses get ownership of government-funded patents found only tepid support, for obvious reasons.

Thus was passed what The Economist called “perhaps the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century.” As a result, most universities created a technology transfer or licensing office to take on their newfound invention-commercialization responsibilities.

What does a university’s Tech Transfer Office, or TTO, actually do on a daily basis? How has the tech transfer field changed since 1980? For answers to these questions and more, tune in for our next installment in the tech transfer saga.