Academic science is quietly facing a replicability crisis. Even less fun than it sounds, it is a crisis whereby academics are struggling to repeat the published results from other laboratories.

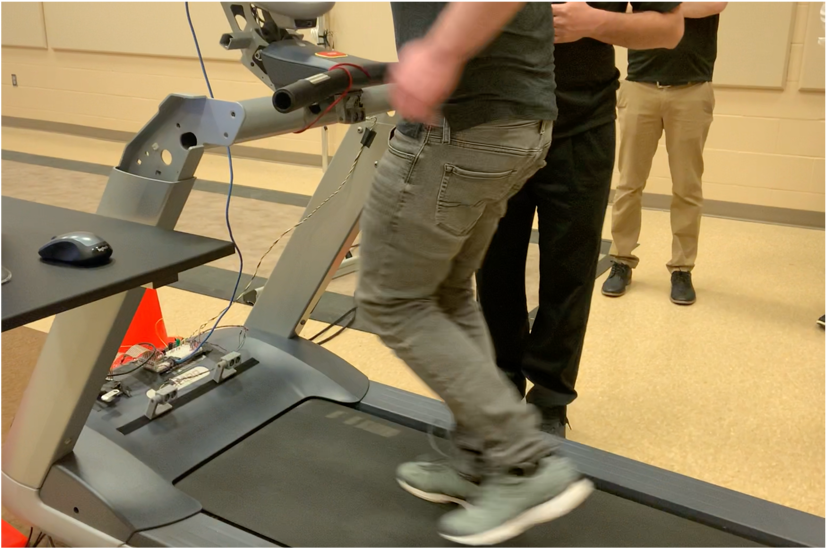

A runner demonstrates how to use the Impower Treadmill in the Biomechanics Lab at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

The Impower Treadmill, successfully relocated to the offices of the Burlington Capital where it was demonstrated to supporters and funders in May.

I was facing the crisis before it was cool.

I started out my career marketing innovation at UNeMed, the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s local technology transfer office. More than twice a company would express interest. We’d do the paperwork and mail a prototype or ship a test tube of something for the interested company to test. Then the test would fail. Our interested commercial laboratory simply couldn’t repeat the published results from the laboratory.

It’s easy to blame in that scenario. Impulsively I wanted to look at the inventor, with a raised eyebrow, and ask to see their lab notebook. With hindsight and a little perspective, I now see the problem more for what it is. In my experience, part of the replicability crisis is in our expectation of what it takes to replicate results. It’s often not the sort of thing you can always just write down. My younger self was a bit naïve – a frozen test tube and list of instructions often weren’t enough.

Take Impower Health, for example. When we initially started working with Doug Miller, I appreciated his skeptical engineer nature and voluminous experience in building fitness equipment. What surprised me was the amount of work and direction it took to facilitate the technology transfer from the University of Nebraska Omaha’s brilliant Biomechanics prototyping and engineering laboratory and the veteran team of fitness engineers at Impower. It was a lot of meetings, a lot of documentation, and an intentional process of try, fail, repeat. I was shocked by the degree of uncertainty that haunted us at every step – can Impower reproduce what the laboratory is conducting?

This spring I got my answer. With UNeTech providing only a wireless mouse, Doug Miller and WP Engine’s VP of Product Ben Jackson were able to boot up and run a prototype Impower treadmill in the luxurious offices of Burlington Capital. The success of that event took more than a detailed instruction manual – it took the creation of an organization. Repeating innovative work takes a culture of people that can make a difficult problem work. Impower, with the support of UNeTech, had to push through so many challenges to repeat the innovative and well-documented work produced by UNO Biomechanics.

The replicability crisis matters. The bedrock of peer review is that published results are reporting an objective phenomenon that can be reproduced. The crisis may not stem from shoddy science or poor design but the unexpected cost of understanding the original research and creating the organizational structure to replicate the results. If UNeTech’s experience with Impower Health is any predictor – it is an expensive process but entirely worth the effort.

Replicability isn’t going to solve itself. Blaming big science probably won’t either. Public faith in institutions, including peer-reviewed, scientific research, is at a dangerous low. My experience, where the tech meets the transfer, leads me to a bracing conclusion: sometimes you need a culture of people dedicated to making replication work.

That, of course, is not a solution. Replication needs to be impassive. It needs to repeat results without care for the outcome. I am all for scientific objectivity. With a few startups under my belt, however, it seems a bit out of touch with the enormously hard work it takes to repeat success: let alone improve and scale it.