Part 4: “And by golly, we got funded”: Gary Hendrix and the first SBIR Success Story

In this series, Jace Gatzemeyer discusses the history, legacy, goals, successes, and shortcomings of the SBIR and STTR programs. Dr. Gatzemeyer is UNeTech’s Grant Writer, and one aspect of his job involves creating strong SBIR/STTR proposals for small businesses in the incubator. This fourth installment looks at the early story of Symantec, the first SBIR awardee.

In 1977, Gary Hendrix and his friends were looking for a way to make a little extra cash. They thought the kind of technology they were creating was “about to get hot.”[1] They were right. Luckily for them, the federal government was about to provide the spark.

A few years previous, while completing his PhD in computer science at the University of Texas, Hendrix had published a paper on computational linguistics and artificial intelligence. His paper caught the attention of some researchers at SRI International, who hired him before he had even completed his degree. One of the nation’s leading scientific research institutes, SRI (formerly affiliated with Stanford University) was on the cutting edge of computing in the 1970s. Inkjet printing (1961), optical disc recording (1963), the computer mouse (1964), an Internet precursor (1969) — all had been pioneered at SRI.

Hendrix worked on natural language processing at SRI, “trying to get computers to understand naturally-occurring languages like English or French or German, as opposed to artificial languages like COBOL or C or FORTRAN or SQL.” In the days before computers had graphical interfaces, you had to give them commands, asking them to do things for you, like run a program or retrieve information from a database. Being able to give commands in plain English would democratize the computer, Hendrix thought, making it accessible to regular people, who probably didn’t know anything about computer programming languages. And with expanded accessibility, the computer would become eminently commercializable.

In 1977 there was general feeling at SRI that several advances in artificial intelligence research were converging and advancing rapidly. “There were a couple of hall conversations about ‘We really ought to talk about what we could do. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could increase our income by ten percent or something just to have a little extra money?’” said Hendrix. “So we started meeting over at my house on Tuesday nights.” As a result, Hendrix and fifteen other like-minded SRI colleagues in 1979 formed Machine Intelligence Corporation, each putting up five thousand dollars to get the business going. They didn’t quit their jobs quite yet, but they had begun their own company.

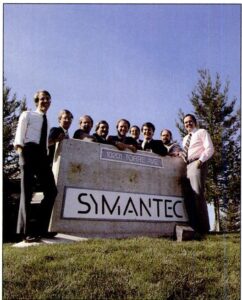

Symantec founders and backers (left to right): John Doerr and Jim Lally, general partners, Kleiner, Perkins; Carl Carman, the Master’s Fund; Jim Peterson, vice president of finance; Gary Hendrix, vice president of technology; Vern Raburn, president; Rod Turner, vice president of marketing; Gordon Eubanks, chairman; Denis Coleman, vice president of development

What would this company do? There was a suggestion that the “most doable” project might be to create a robotic vision system. But at this point the SBIR program intervened. It was 1979, and the National Science Foundation had just released its second solicitation in the pilot program for the Small Business Innovation Research program, which was a new effort to support small businesses in conducting high-tech research and development that would advance the state of the art and simulate the American economy. The direction of the company, Hendrix explained, was ultimately determined by the discovery of that opportunity:

Charlie [Rosen] was all excited because one of his friends at the National Science Foundation had sent him a solicitation for a new program they had called the Small Business Innovative [sic] Research Program… You could get a whopping twenty-five thousand dollars in Phase I money if you could do something interesting… [and] if you did well and you won the competition, in the next round you could get a quarter of a million dollars. So this was Tuesday night…and the proposals were due in Washington by 10 a.m. on Friday… So we set up shop in my living room and we wrote a very, very nice proposal… And by golly we got funded.

The SBIR proposal from Machine Intelligence Corporation did not involve robotic vision, however; rather, their proposal responded to the NSF’s solicitation for products that would improve manufacturing. Hendrix and his colleagues proposed to apply natural language computing to the manufacturing process. And they succeeded. “[We] wrote a nice little system that ran on the Apple II,” said Hendrix, “and by golly it would parse sentences and it would come out with the types of structures that we would need to go to a database.” On the strength of this work, the NSF granted Machine Intelligence a Phase II award of $220,000, which arrived in the summer of 1981 — at which point Hendrix decided it was finally time to quit at SRI and work full time at Machine Intelligence.

Like so many Silicon Valley startups before it, Machine Intelligence folded within a few months, but Hendrix soldiered on, creating his own company in 1982, which he called Symantec (a play on the words “syntax,” “semantic,” and “tech”). Using Phase II funding from the NSF, Hendrix laid the foundation for an advanced natural language database system that would become Symantec’s first product, Q&A, released in 1985. Q&A was a database and word processing software program with a natural language search function, meaning questions about the database could be asked and answered in English rather than programming jargon. It was a big step toward making computers less intimidating, and it generated $1.4 million in 1985 alone.

Symantec was off and running. Through the late 1980s, it released several more products and made lots more money. By the time the company went public in 1989, Q&A still represented one-third of Symantec’s $50 million in revenue. Today, the company is known as NortonLifeLock Inc. and is worth $14.97 billion.

And it all began with an SBIR grant.

Hear the story in Gary Hendrix’s own words.

In a future blog post, we’ll get back to the legislative history of the SBIR program. Before that, however, I’ll follow up on the last installment’s promise to cover SBIR/STTR from the perspective of the COVID-19 pandemic. What has the pandemic revealed about the power of cooperation between the government and small businesses? What role does the government have to guide and bolster the economy? Does capitalism thrive or decline when governments absorb economic risk? To read about all this and more, check out our next post.

[1] Quotations from Gary Hendrix are taken from his 19 November 2004 interview with the Computer History Museum: http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Oral_History/Hendrix_Gary/Hendrix_Gary.oral_history.2004.102657945.pdf.